The Futurist Manifesto

F. T. Marinetti, 1909

We have been up all night, my friends and I, beneath mosque lamps whose brass cupolas are bright as our souls, because like them they were illuminated by the internal glow of electric hearts. And trampling underfoot our native sloth on opulent Persian carpets, we have been discussing right up to the limits of logic and scrawling the paper with demented writing.

Our hearts were filled with an immense pride at feeling ourselves standing quite alone, like lighthouses or like the sentinels in an outpost, facing the army of enemy stars encamped in their celestial bivouacs. Alone with the engineers in the infernal stokeholes of great ships, alone with the black spirits which rage in the belly of rogue locomotives, alone with the drunkards beating their wings against the walls.

Then we were suddenly distracted by the rumbling of huge double decker trams that went leaping by, streaked with light like the villages celebrating their festivals, which the Po in flood suddenly knocks down and uproots, and, in the rapids and eddies of a deluge, drags down to the sea.

Then the silence increased. As we listened to the last faint prayer of the old canal and the crumbling of the bones of the moribund palaces with their green growth of beard, suddenly the hungry automobiles roared beneath our windows.

`Come, my friends!' I said. `Let us go! At last Mythology and the mystic cult of the ideal have been left behind. We are going to be present at the birth of the centaur and we shall soon see the first angels fly! We must break down the gates of life to test the bolts and the padlocks! Let us go! Here is they very first sunrise on earth! Nothing equals the splendor of its red sword which strikes for the first time in our millennial darkness.'

We went up to the three snorting machines to caress their breasts. I lay along mine like a corpse on its bier, but I suddenly revived again beneath the steering wheel - a guillotine knife - which threatened my stomach. A great sweep of madness brought us sharply back to ourselves and drove us through the streets, steep and deep, like dried up torrents. Here and there unhappy lamps in the windows taught us to despise our mathematical eyes. `Smell,' I exclaimed, `smell is good enough for wild beasts!'

And we hunted, like young lions, death with its black fur dappled with pale crosses, who ran before us in the vast violet sky, palpable and living.

And yet we had no ideal Mistress stretching her form up to the clouds, nor yet a cruel Queen to whom to offer our corpses twisted into the shape of Byzantine rings! No reason to die unless it is the desire to be rid of the too great weight of our courage!

We drove on, crushing beneath our burning wheels, like shirt-collars under the iron, the watch dogs on the steps of the houses.

Death, tamed, went in front of me at each corner offering me his hand nicely, and sometimes lay on the ground with a noise of creaking jaws giving me velvet glances from the bottom of puddles.

`Let us leave good sense behind like a hideous husk and let us hurl ourselves, like fruit spiced with pride, into the immense mouth and breast of the world! Let us feed the unknown, not from despair, but simply to enrich the unfathomable reservoirs of the Absurd!'

Thursday, October 18, 2007

Monday, October 1, 2007

Ogden Nash

Very Like a Whale

Ogden Nash

One thing that Literature would be greatly the better for

Would be a more restricted employment by authors of simile and metaphor.

Authors of all races, be they Greeks, Romans, Teutons or Celts,

Can't seem just to say that anything is the thing it is but have to go out of their way to say it is like something else.

What does it mean when we are told

That the Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold?

In the first place, George Gordon Byron had had enough experience

To know that it probably wasn't just one Assyrian, it was a lot of Assyrians.

However, as so many arguments are apt to induce apoplexy and thus hinder longevity,

We'll let it pass as one Assyrian for the sake of brevity.

Now then, this particular Assyrian, the one whose cohorts were

gleaming in purple and gold,

Just what does the poet mean when he says he came down like a wolf on the fold?

In heaven and earth more than is dreamed of in our philosophy there are great many things,

But I don't imagine that among them there is a wolf with purple

and gold cohorts or purple and gold anythings.

No, no, Lord Byron, before I'll believe that this Assyrian was actually like a wolf I must have some kind of proof;

Did he run on all fours and did he have a hairy tail and a big red mouth and big white teeth and did he say

Woof woof?

Frankly I think it very unlikely, and all you were entitled to say, at the very most,

Was that the Assyrian cohorts came down like a lot of Assyrian cohorts about to destroy the Hebrew host.

But that wasn't fancy enough for Lord Byron, oh dear me no, he had to invent a lot of figures of speech and then interpolate them,

With the result that whenever you mention Old Testament soldiers to people they say,

Oh yes, they're the ones that a lot of wolves dressed up in gold and purple ate them.

That's the kind of thing that's being done all the time by poets, from Homer to Tennyson;

They're always comparing ladies to lilies and veal to venison,

And they always say things like that the snow is a white blanket after a winter storm.

Oh it is, is it, all right then, you sleep under a six-inch blanket of snow and

I'll sleep under a half-inch blanket of unpoetical

blanket material and we'll see which one keeps warm,

And after that maybe you'll begin to comprehend dimly

What I mean by too much metaphor and simile.

Ogden Nash

One thing that Literature would be greatly the better for

Would be a more restricted employment by authors of simile and metaphor.

Authors of all races, be they Greeks, Romans, Teutons or Celts,

Can't seem just to say that anything is the thing it is but have to go out of their way to say it is like something else.

What does it mean when we are told

That the Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold?

In the first place, George Gordon Byron had had enough experience

To know that it probably wasn't just one Assyrian, it was a lot of Assyrians.

However, as so many arguments are apt to induce apoplexy and thus hinder longevity,

We'll let it pass as one Assyrian for the sake of brevity.

Now then, this particular Assyrian, the one whose cohorts were

gleaming in purple and gold,

Just what does the poet mean when he says he came down like a wolf on the fold?

In heaven and earth more than is dreamed of in our philosophy there are great many things,

But I don't imagine that among them there is a wolf with purple

and gold cohorts or purple and gold anythings.

No, no, Lord Byron, before I'll believe that this Assyrian was actually like a wolf I must have some kind of proof;

Did he run on all fours and did he have a hairy tail and a big red mouth and big white teeth and did he say

Woof woof?

Frankly I think it very unlikely, and all you were entitled to say, at the very most,

Was that the Assyrian cohorts came down like a lot of Assyrian cohorts about to destroy the Hebrew host.

But that wasn't fancy enough for Lord Byron, oh dear me no, he had to invent a lot of figures of speech and then interpolate them,

With the result that whenever you mention Old Testament soldiers to people they say,

Oh yes, they're the ones that a lot of wolves dressed up in gold and purple ate them.

That's the kind of thing that's being done all the time by poets, from Homer to Tennyson;

They're always comparing ladies to lilies and veal to venison,

And they always say things like that the snow is a white blanket after a winter storm.

Oh it is, is it, all right then, you sleep under a six-inch blanket of snow and

I'll sleep under a half-inch blanket of unpoetical

blanket material and we'll see which one keeps warm,

And after that maybe you'll begin to comprehend dimly

What I mean by too much metaphor and simile.

Sunday, September 2, 2007

Japser Johns

Portrait of a Lady

She appeared to have, in her experience, a touchstone for everything, and somewhere in the capacious pocket of her genial memory she would find the key to Henrietta's virtue. "That is the great thing," Isabel reflected; "that is the supreme good fortune: to be in a better position for appreciating people than they are for appreciating you."

-Henry James. The Portrait of a Lady.

-Henry James. The Portrait of a Lady.

Saturday, August 25, 2007

Waller and Pound

"Go, Lovely Rose!"

Go, lovely rose!

Tell her, that wastes her time and me,

That now she knows

When I resemble her to thee,

How sweet and fair she seems to be.

Tell her that's young

And shuns to have her graces spied

That hadst thou sprung

In deserts, where no men abide

Thou must have uncommended died.

Small is the worth

Of beauty from the light retired:

Bid her come forth,

Suffer herself to be desired,

And not blush so to be admired.

Then die! that she

The common fate of all things rare

May read in thee:

How small a part of time they share

That are so wondrous, sweet and fair!

-Edmund Waller (1600-87)

Envoi

Go, dumb-born book

Tell her that sang me once the song of Lawes:

Hadst thou but song

As thou hast subjects known,

Then were there cause in thee that should condone

Even my faults that heavy upon me lie

And build her glories their longevity.

Tell her that sheds

Such treasure in the air

Recking naught else but that her graces give

Life to the moment

I would bid them live

As roses might, in magic amber laid,

Red overwrought with orange and all made

One substance and one colour

Braving time.

Tell her that goes

With song upon her lips

But sings not out the song, nor knows

The maker of it, some other mouth

May be as fair as hers,

Might, in new ages, gain her worshippers

When our two dusts with Waller's shall be laid,

Siftings on siftings into oblivion

Till change hath broken down

All things save Beauty alone.

-Ezra Pound (1885-1972)

Go, lovely rose!

Tell her, that wastes her time and me,

That now she knows

When I resemble her to thee,

How sweet and fair she seems to be.

Tell her that's young

And shuns to have her graces spied

That hadst thou sprung

In deserts, where no men abide

Thou must have uncommended died.

Small is the worth

Of beauty from the light retired:

Bid her come forth,

Suffer herself to be desired,

And not blush so to be admired.

Then die! that she

The common fate of all things rare

May read in thee:

How small a part of time they share

That are so wondrous, sweet and fair!

-Edmund Waller (1600-87)

Envoi

Go, dumb-born book

Tell her that sang me once the song of Lawes:

Hadst thou but song

As thou hast subjects known,

Then were there cause in thee that should condone

Even my faults that heavy upon me lie

And build her glories their longevity.

Tell her that sheds

Such treasure in the air

Recking naught else but that her graces give

Life to the moment

I would bid them live

As roses might, in magic amber laid,

Red overwrought with orange and all made

One substance and one colour

Braving time.

Tell her that goes

With song upon her lips

But sings not out the song, nor knows

The maker of it, some other mouth

May be as fair as hers,

Might, in new ages, gain her worshippers

When our two dusts with Waller's shall be laid,

Siftings on siftings into oblivion

Till change hath broken down

All things save Beauty alone.

-Ezra Pound (1885-1972)

Thursday, August 16, 2007

Matthew Arnold

"The freethinking of one age is the common sense of the next."

-Matthew Arnold. 1822-1888.

-Matthew Arnold. 1822-1888.

Friday, August 10, 2007

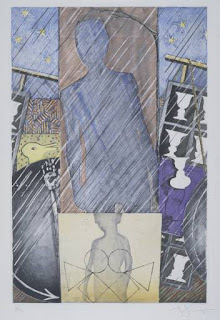

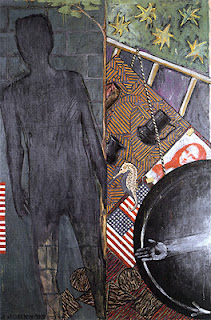

Jasper Johns The Seasons

Spring

Winter

FOR some months now, the recent four-part cycle of paintings by Jasper Johns called ''The Seasons'' has been spoken of by those who have seen it in private as a benchmark in the history not only of American art, but of American autobiography. Now that ''The Seasons'' can be seen through March 7 at the Leo Castelli Gallery, 420 West Broadway, at Spring Street, it is clear that this was not an exaggeration.

After the exhibition is over, the four big paintings will go their separate ways. The same is true of the large group of drawings, watercolors and prints, all of them closely related to ''The Seasons'' and many of them of capital importance. It therefore goes without saying that this show is a one-time-only event and should on no account be missed. It proves, among much else, that difficult and demanding major art can still be made in an age that loves to flirt with work that is as flimsy as it is immediate.

Like everything else that Johns has done over the last 30-and-more years, ''The Seasons'' is sometimes oblique and riddlesome and at other times disconcertingly direct. The four big paintings - each of them measuring 75 by 50 inches - deal with the given, as distinct from the invented. The given, in this sense, has preoccupied Johns. Ever since, he made his debut in 1955, he has painted subject matter that was not merely given but immutable, like the American flag. Even the title of his new cycle is given, after all, for what could be closer to tradition than a series of paintings called ''Spring,'' ''Summer,'' ''Fall'' and ''Winter''? Nor does Johns stint on seasonal details that likewise can be taken for granted, like the look of the leaves on the tree in ''Spring'' and ''Summer'' and the outline of the snowman in ''Winter.''

As Leo Steinberg pointed out as long ago as 1962, Jasper Johns has constantly relied for his subject matter on ''commonplaces of our environment, which possess a ritual or conventional shape, not to be altered.'' But what was read at the time as an

annihilation of the self, or as an anti-autobiography, has turned out with time to be fraught with private meaning. More recently, and notably in the paintings that made up his  last New York show in 1984, he has undertaken what might be called a symphonic stocktaking. Things dear to him are listed, pored over, set down on the canvas in an idiom that is both rich and dense, and thereafter combined and recombined.

last New York show in 1984, he has undertaken what might be called a symphonic stocktaking. Things dear to him are listed, pored over, set down on the canvas in an idiom that is both rich and dense, and thereafter combined and recombined.

last New York show in 1984, he has undertaken what might be called a symphonic stocktaking. Things dear to him are listed, pored over, set down on the canvas in an idiom that is both rich and dense, and thereafter combined and recombined.

last New York show in 1984, he has undertaken what might be called a symphonic stocktaking. Things dear to him are listed, pored over, set down on the canvas in an idiom that is both rich and dense, and thereafter combined and recombined. The notion of the given is still very much there, and never more so than in ''The Seasons'' and its related smaller works. It is, however, presented in a new context. As both Judith Goldman and Barbara Rose have pointed out in print, ''The Seasons'' is about a moving house, and is directly related to a painting by Picasso, dated 1955, called ''The Minotaur Moving His House.''

As Johns has recently acquired two new houses, there was an evident aptness about the image of Picasso's Minotaur piling his possessions on a cart and hauling it along. On that cart are a large painting, secured with rope, and a ladder. (The Minotaur is not usually thought of as an ardent collector, but Picasso told the photographer David Douglas Duncan that this particular painting was one he couldn't bear to leave behind.) Both rope and ladder recur throughout ''The Seasons,'' together with paintings or parts of paintings by Johns himself. There are also echoes and reprises of material already familiar to students of his work but here given a whole new significance. He does not, however, double as the fresh-faced Minotaur that we see in the Picasso. Instead, and with characteristic obliquity, he portrays himself in terms of an outline drawing of his shadow that was prepared for him by a painter friend.

As Johns has recently acquired two new houses, there was an evident aptness about the image of Picasso's Minotaur piling his possessions on a cart and hauling it along. On that cart are a large painting, secured with rope, and a ladder. (The Minotaur is not usually thought of as an ardent collector, but Picasso told the photographer David Douglas Duncan that this particular painting was one he couldn't bear to leave behind.) Both rope and ladder recur throughout ''The Seasons,'' together with paintings or parts of paintings by Johns himself. There are also echoes and reprises of material already familiar to students of his work but here given a whole new significance. He does not, however, double as the fresh-faced Minotaur that we see in the Picasso. Instead, and with characteristic obliquity, he portrays himself in terms of an outline drawing of his shadow that was prepared for him by a painter friend.

-"The Seasons": Forceful Painting by Jasper Johns. By John Russell. In the New York Times February 6, 1987

Fall

The Little White Bird

Because I knew the maid, she was mine. Every maid, I say, is for him who can know her. The others had but followed the glamour in which she walked, but I had pierced it and found the woman. I could anticipate her every thought and gesture, I could have flashed and rippled and mocked for her, and melted for her and been dear disdain for her. She would forget this and suddenly be conscious of it as she began to speak, when she gave me a look with a shy smile in it which meant that she knew I was already waiting at the end of what she had to say. I call this the blush of the eye. She had a look and a voice that were for me alone; her very finger-tips were charged with caresses for me. And I loved even her naughtiness, as when she stamped her foot at me, which she could not do without gnashing her teeth, like a child trying to look fearsome. How pretty was that gnashing of her teeth! All her tormentings of me turned suddenly into sweetnes, and who could torment like an exquisite fury, wondering in sudden flame why she could give herself to anyone, while I wondered only why she could give herself to me. It may be that I wondered overmuch. Perhaps that was why I lost her.

...I am not that man, for, mystery of mysteries, I lost her. I know not how it was, though in the twilight of my life that then began I groped for reasons until I wearied of myself; all I know is that she had ceased to love me; the discovery came to me slowly, as if I were a most dull-witted man; at first I knew only that I no longer understood her as of old.

-J.M. Barrie. The Little White Bird. 86.

...I am not that man, for, mystery of mysteries, I lost her. I know not how it was, though in the twilight of my life that then began I groped for reasons until I wearied of myself; all I know is that she had ceased to love me; the discovery came to me slowly, as if I were a most dull-witted man; at first I knew only that I no longer understood her as of old.

-J.M. Barrie. The Little White Bird. 86.

Wednesday, June 6, 2007

Oscar Wilde

From The Critic as Artist,

with some remarks on the importance of doing nothing (1890):

Gilbert:...Education is an admirable thing, but it is well to remember from time to time that nothing that is worth knowing can be taught. Through the parted curtains of the window I see the moon like a clipped piece of silver. Like gilded bees the stars cluster round her. The sky is a hard hollow sapphire. Let us go out into the night. Thought is wonderful, but adventure is more wonderful still. Who knows but we may meet Prince Florizel of Bohemia, and hear the fair Cuban tell us that she is not what she seems?

Symphony in Yellow (1889)

An omnibus across the bridge

Crawls like a yellow butterfly,

And, here and there, a passer-by

Shows like a little restless midge.

Big barges full of yellow hay

Are moved against the shadowy wharf,

And, like a yellow silken scarf,

The thick fog hangs along the quay.

The yellow leaves beging to fade

And flutter from the Temple elms,

And at my feet the pale green Thames

Lies like a rod of rippled jade.

with some remarks on the importance of doing nothing (1890):

Gilbert:...Education is an admirable thing, but it is well to remember from time to time that nothing that is worth knowing can be taught. Through the parted curtains of the window I see the moon like a clipped piece of silver. Like gilded bees the stars cluster round her. The sky is a hard hollow sapphire. Let us go out into the night. Thought is wonderful, but adventure is more wonderful still. Who knows but we may meet Prince Florizel of Bohemia, and hear the fair Cuban tell us that she is not what she seems?

Symphony in Yellow (1889)

An omnibus across the bridge

Crawls like a yellow butterfly,

And, here and there, a passer-by

Shows like a little restless midge.

Big barges full of yellow hay

Are moved against the shadowy wharf,

And, like a yellow silken scarf,

The thick fog hangs along the quay.

The yellow leaves beging to fade

And flutter from the Temple elms,

And at my feet the pale green Thames

Lies like a rod of rippled jade.

Thursday, May 31, 2007

Arthur Symons

From A Prelude to Life (1905):

If there ever was a religion of the eyes, I have devoutly practiced that religion. I noted every face that passed me on the pavement; I looked into the omnibuses, the cabs, always with the same eager hope of seeing some beautiful or interesting person, some gracious movement, a delicate expression, which would be gone if I did not catch it as it went. The search without an aim grew almost a torture to me...I grasped at all these sights with the same futile energy as a dog that I once saw standing in an Irish stream, and snapping at the bubbles that ran continually past him on the water. Life ran past me continually, and I tried to make all its bubbles my own.

Nerves (1897):

A modern malady of love is nerves.

Love, once a simple madness, now observes

The stages of his passionate disease,

And is twice sorrowful because he sees

Inch by inch entering, the fatal knife.

O health of simple minds, give me your life,

And let me, for one midnight, cease to hear

The clock for ever ticking in my ear,

The clock that tells the minutes in my brain.

It is not love, nor love's despair, this pain

That shoots a witless, keener pain across

The simple agony of love and loss.

Nerves, nerves! O folly of a child who dreams

Of heaven, and, waking in the darkness, screams.

If there ever was a religion of the eyes, I have devoutly practiced that religion. I noted every face that passed me on the pavement; I looked into the omnibuses, the cabs, always with the same eager hope of seeing some beautiful or interesting person, some gracious movement, a delicate expression, which would be gone if I did not catch it as it went. The search without an aim grew almost a torture to me...I grasped at all these sights with the same futile energy as a dog that I once saw standing in an Irish stream, and snapping at the bubbles that ran continually past him on the water. Life ran past me continually, and I tried to make all its bubbles my own.

Nerves (1897):

A modern malady of love is nerves.

Love, once a simple madness, now observes

The stages of his passionate disease,

And is twice sorrowful because he sees

Inch by inch entering, the fatal knife.

O health of simple minds, give me your life,

And let me, for one midnight, cease to hear

The clock for ever ticking in my ear,

The clock that tells the minutes in my brain.

It is not love, nor love's despair, this pain

That shoots a witless, keener pain across

The simple agony of love and loss.

Nerves, nerves! O folly of a child who dreams

Of heaven, and, waking in the darkness, screams.

Sunday, May 27, 2007

La Peste Marginalia

Slowing down time:

« Question: comment faire pour ne pas perdre son temps? Réponse : l’éprouver dans toutes sa longueur. Moyens : passer des journées dans l’antichambre d’un dentiste, sur une chaise inconfortable ; vivre à son balcon le dimanche après-midi ; écouter des conférences dans une langue qu’on ne comprend pas, choisir les intinéraires de chemin de fer plus longs et les plus commodes et voyager debout naturellement ; faire la queue aux guichets des spectacles et ne pas prendre sa place, etc. »

-La Peste. Albert Camus

« Question: comment faire pour ne pas perdre son temps? Réponse : l’éprouver dans toutes sa longueur. Moyens : passer des journées dans l’antichambre d’un dentiste, sur une chaise inconfortable ; vivre à son balcon le dimanche après-midi ; écouter des conférences dans une langue qu’on ne comprend pas, choisir les intinéraires de chemin de fer plus longs et les plus commodes et voyager debout naturellement ; faire la queue aux guichets des spectacles et ne pas prendre sa place, etc. »

-La Peste. Albert Camus

Monday, May 21, 2007

Garamond Marginalia

Monotype Garamond

Monotype Garamond is a design of remarkable sophistication, and is certainly one of the most elegant interpretations of the Garamond type style. With its distinct contrast in stroke weights, open counters and delicate serifs, Monotype Garamond is exceptionally legible and can be set at virtually any size. The contrast between the Roman and Bold weights is nothing short of ideal.

Such an exemplary type revival is, of course, a tribute to the excellence of the model. As it turns out, the model in this case was inspired – but not designed – by Claude Garamond.

It was under Stanley Morison’s leadership, in the third decade of the twentieth century, that Monotype undertook the most aggressive program of typeface development ever attempted in Europe up to that time. The program encompassed original typefaces and interpretations of old designs. It would ultimately produce such faces as Centaur, Gill Sans, Perpetua, and Ehrhardt, as well as Monotype’s versions of Bembo, Baskerville, Fournier and of course, Garamond.

Cut in 1922, Monotype Garamond was the first of Morison’s celebrated typeface revivals. It was patterned after type from the archives of the French Imprimerie Nationale, the centuries-old office of French government printing (broadly equivalent to the US Government Printing Office, or Her Majesty’s Stationery Office in the UK).

The Imprimerie type was long believed to be the early-16th-century work of Claude Garamond. It was only in 1926, after “Garamond” fonts from Monotype and many other foundries had been released, that type historian Beatrice Warde discovered the type was the work of Jean Jannon, of Sedan, France. Jannon was a later designer who produced his work some eighty years after the fonts of Garamond. (In an added twist to this mistaken-identity plot, Warde published her discovery under the pseudonym “Paul Beaujon.”)

Jannon’s goal, much like Monotype’s three centuries later, was to imitate the style of the great masters of roman type and make their designs available to printers of his own day. Obviously, he succeeded. The French Imprimerie purchased his types and, over time, as the name of Jean Jannon faded, came to believe they were indeed fonts from the earlier master punch cutter.

Monotype Garamond is a design of remarkable sophistication, and is certainly one of the most elegant interpretations of the Garamond type style. With its distinct contrast in stroke weights, open counters and delicate serifs, Monotype Garamond is exceptionally legible and can be set at virtually any size. The contrast between the Roman and Bold weights is nothing short of ideal.

Such an exemplary type revival is, of course, a tribute to the excellence of the model. As it turns out, the model in this case was inspired – but not designed – by Claude Garamond.

It was under Stanley Morison’s leadership, in the third decade of the twentieth century, that Monotype undertook the most aggressive program of typeface development ever attempted in Europe up to that time. The program encompassed original typefaces and interpretations of old designs. It would ultimately produce such faces as Centaur, Gill Sans, Perpetua, and Ehrhardt, as well as Monotype’s versions of Bembo, Baskerville, Fournier and of course, Garamond.

Cut in 1922, Monotype Garamond was the first of Morison’s celebrated typeface revivals. It was patterned after type from the archives of the French Imprimerie Nationale, the centuries-old office of French government printing (broadly equivalent to the US Government Printing Office, or Her Majesty’s Stationery Office in the UK).

The Imprimerie type was long believed to be the early-16th-century work of Claude Garamond. It was only in 1926, after “Garamond” fonts from Monotype and many other foundries had been released, that type historian Beatrice Warde discovered the type was the work of Jean Jannon, of Sedan, France. Jannon was a later designer who produced his work some eighty years after the fonts of Garamond. (In an added twist to this mistaken-identity plot, Warde published her discovery under the pseudonym “Paul Beaujon.”)

Jannon’s goal, much like Monotype’s three centuries later, was to imitate the style of the great masters of roman type and make their designs available to printers of his own day. Obviously, he succeeded. The French Imprimerie purchased his types and, over time, as the name of Jean Jannon faded, came to believe they were indeed fonts from the earlier master punch cutter.

Saturday, May 19, 2007

VIS Marginalia I

In the midst of a 15-minute phone conversation with a partially deaf 80-year-old Stanford Law School graduate: "You call that rinky-dink soccer field a stadium? Is that what you call it? You know that Stanford killed my dream and shot themselves in the foot when they built that rinky-dink piece of crap? Now we'll never have the Olympics at Stanford. No, we won't, not with that piece of junk. That's what I call it, a piece of crap, because they killed my dream. We had a beautiful stadium with a track where we could hold the Olympics, and now..."

10 minutes later....

"I'm sorry, sir, I have to let you go. There are other visitors here..."

"No, my speech is finished."

At Hoover Tower:

A Stanford graduate student: "Is it true that Leland Stanford had two illegitimate Chinese children?"

A middle-aged female visitor in the elevator: "So what sort of reputation does Leland Stanford have on campus? Do people think of him as a crook or what? I mean, Andrew Carnegie gave money to libraries, but he was not a nice guy."

10 minutes later....

"I'm sorry, sir, I have to let you go. There are other visitors here..."

"No, my speech is finished."

At Hoover Tower:

A Stanford graduate student: "Is it true that Leland Stanford had two illegitimate Chinese children?"

A middle-aged female visitor in the elevator: "So what sort of reputation does Leland Stanford have on campus? Do people think of him as a crook or what? I mean, Andrew Carnegie gave money to libraries, but he was not a nice guy."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)