"Go, Lovely Rose!"

Go, lovely rose!

Tell her, that wastes her time and me,

That now she knows

When I resemble her to thee,

How sweet and fair she seems to be.

Tell her that's young

And shuns to have her graces spied

That hadst thou sprung

In deserts, where no men abide

Thou must have uncommended died.

Small is the worth

Of beauty from the light retired:

Bid her come forth,

Suffer herself to be desired,

And not blush so to be admired.

Then die! that she

The common fate of all things rare

May read in thee:

How small a part of time they share

That are so wondrous, sweet and fair!

-Edmund Waller (1600-87)

Envoi

Go, dumb-born book

Tell her that sang me once the song of Lawes:

Hadst thou but song

As thou hast subjects known,

Then were there cause in thee that should condone

Even my faults that heavy upon me lie

And build her glories their longevity.

Tell her that sheds

Such treasure in the air

Recking naught else but that her graces give

Life to the moment

I would bid them live

As roses might, in magic amber laid,

Red overwrought with orange and all made

One substance and one colour

Braving time.

Tell her that goes

With song upon her lips

But sings not out the song, nor knows

The maker of it, some other mouth

May be as fair as hers,

Might, in new ages, gain her worshippers

When our two dusts with Waller's shall be laid,

Siftings on siftings into oblivion

Till change hath broken down

All things save Beauty alone.

-Ezra Pound (1885-1972)

Saturday, August 25, 2007

Thursday, August 16, 2007

Matthew Arnold

"The freethinking of one age is the common sense of the next."

-Matthew Arnold. 1822-1888.

-Matthew Arnold. 1822-1888.

Friday, August 10, 2007

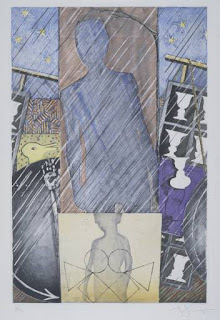

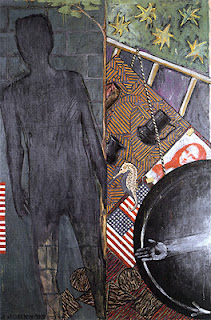

Jasper Johns The Seasons

Spring

Winter

FOR some months now, the recent four-part cycle of paintings by Jasper Johns called ''The Seasons'' has been spoken of by those who have seen it in private as a benchmark in the history not only of American art, but of American autobiography. Now that ''The Seasons'' can be seen through March 7 at the Leo Castelli Gallery, 420 West Broadway, at Spring Street, it is clear that this was not an exaggeration.

After the exhibition is over, the four big paintings will go their separate ways. The same is true of the large group of drawings, watercolors and prints, all of them closely related to ''The Seasons'' and many of them of capital importance. It therefore goes without saying that this show is a one-time-only event and should on no account be missed. It proves, among much else, that difficult and demanding major art can still be made in an age that loves to flirt with work that is as flimsy as it is immediate.

Like everything else that Johns has done over the last 30-and-more years, ''The Seasons'' is sometimes oblique and riddlesome and at other times disconcertingly direct. The four big paintings - each of them measuring 75 by 50 inches - deal with the given, as distinct from the invented. The given, in this sense, has preoccupied Johns. Ever since, he made his debut in 1955, he has painted subject matter that was not merely given but immutable, like the American flag. Even the title of his new cycle is given, after all, for what could be closer to tradition than a series of paintings called ''Spring,'' ''Summer,'' ''Fall'' and ''Winter''? Nor does Johns stint on seasonal details that likewise can be taken for granted, like the look of the leaves on the tree in ''Spring'' and ''Summer'' and the outline of the snowman in ''Winter.''

As Leo Steinberg pointed out as long ago as 1962, Jasper Johns has constantly relied for his subject matter on ''commonplaces of our environment, which possess a ritual or conventional shape, not to be altered.'' But what was read at the time as an

annihilation of the self, or as an anti-autobiography, has turned out with time to be fraught with private meaning. More recently, and notably in the paintings that made up his  last New York show in 1984, he has undertaken what might be called a symphonic stocktaking. Things dear to him are listed, pored over, set down on the canvas in an idiom that is both rich and dense, and thereafter combined and recombined.

last New York show in 1984, he has undertaken what might be called a symphonic stocktaking. Things dear to him are listed, pored over, set down on the canvas in an idiom that is both rich and dense, and thereafter combined and recombined.

last New York show in 1984, he has undertaken what might be called a symphonic stocktaking. Things dear to him are listed, pored over, set down on the canvas in an idiom that is both rich and dense, and thereafter combined and recombined.

last New York show in 1984, he has undertaken what might be called a symphonic stocktaking. Things dear to him are listed, pored over, set down on the canvas in an idiom that is both rich and dense, and thereafter combined and recombined. The notion of the given is still very much there, and never more so than in ''The Seasons'' and its related smaller works. It is, however, presented in a new context. As both Judith Goldman and Barbara Rose have pointed out in print, ''The Seasons'' is about a moving house, and is directly related to a painting by Picasso, dated 1955, called ''The Minotaur Moving His House.''

As Johns has recently acquired two new houses, there was an evident aptness about the image of Picasso's Minotaur piling his possessions on a cart and hauling it along. On that cart are a large painting, secured with rope, and a ladder. (The Minotaur is not usually thought of as an ardent collector, but Picasso told the photographer David Douglas Duncan that this particular painting was one he couldn't bear to leave behind.) Both rope and ladder recur throughout ''The Seasons,'' together with paintings or parts of paintings by Johns himself. There are also echoes and reprises of material already familiar to students of his work but here given a whole new significance. He does not, however, double as the fresh-faced Minotaur that we see in the Picasso. Instead, and with characteristic obliquity, he portrays himself in terms of an outline drawing of his shadow that was prepared for him by a painter friend.

As Johns has recently acquired two new houses, there was an evident aptness about the image of Picasso's Minotaur piling his possessions on a cart and hauling it along. On that cart are a large painting, secured with rope, and a ladder. (The Minotaur is not usually thought of as an ardent collector, but Picasso told the photographer David Douglas Duncan that this particular painting was one he couldn't bear to leave behind.) Both rope and ladder recur throughout ''The Seasons,'' together with paintings or parts of paintings by Johns himself. There are also echoes and reprises of material already familiar to students of his work but here given a whole new significance. He does not, however, double as the fresh-faced Minotaur that we see in the Picasso. Instead, and with characteristic obliquity, he portrays himself in terms of an outline drawing of his shadow that was prepared for him by a painter friend.

-"The Seasons": Forceful Painting by Jasper Johns. By John Russell. In the New York Times February 6, 1987

Fall

The Little White Bird

Because I knew the maid, she was mine. Every maid, I say, is for him who can know her. The others had but followed the glamour in which she walked, but I had pierced it and found the woman. I could anticipate her every thought and gesture, I could have flashed and rippled and mocked for her, and melted for her and been dear disdain for her. She would forget this and suddenly be conscious of it as she began to speak, when she gave me a look with a shy smile in it which meant that she knew I was already waiting at the end of what she had to say. I call this the blush of the eye. She had a look and a voice that were for me alone; her very finger-tips were charged with caresses for me. And I loved even her naughtiness, as when she stamped her foot at me, which she could not do without gnashing her teeth, like a child trying to look fearsome. How pretty was that gnashing of her teeth! All her tormentings of me turned suddenly into sweetnes, and who could torment like an exquisite fury, wondering in sudden flame why she could give herself to anyone, while I wondered only why she could give herself to me. It may be that I wondered overmuch. Perhaps that was why I lost her.

...I am not that man, for, mystery of mysteries, I lost her. I know not how it was, though in the twilight of my life that then began I groped for reasons until I wearied of myself; all I know is that she had ceased to love me; the discovery came to me slowly, as if I were a most dull-witted man; at first I knew only that I no longer understood her as of old.

-J.M. Barrie. The Little White Bird. 86.

...I am not that man, for, mystery of mysteries, I lost her. I know not how it was, though in the twilight of my life that then began I groped for reasons until I wearied of myself; all I know is that she had ceased to love me; the discovery came to me slowly, as if I were a most dull-witted man; at first I knew only that I no longer understood her as of old.

-J.M. Barrie. The Little White Bird. 86.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)